|

|

|

- Preaching

the Living WORD through the Written WORD - 2 Tim 4:2 - |

|

|

|

“HOW

WE GOT OUT BIBLE” (PART

1 - INSPIRATION) Pastor I. INTRODUCTION A. The Bible is an interesting subject and

almost everyone has an opinion on it. Some good, some not so good, and some

are downright erroneous. Is the Bible the basis for belief and behavior for

mankind, or is it a well-preserved folklore? B. One such disclaimer is Rev. John Shelby

Spong, who says, Can modern men and women continue to pretend that

timeless, eternal, and unchanging truth has been captured in the words of a

book that achieved its final written form midway into the second century of

this common era? (Rescuing the Bible From Fundamentalism). C. How does one determine if the Bible we

hold in our hands is really God's Word or not? How were these early writings

compiled and on what basis? In addition, how do we know that the Bible we

purchase from the shelf of a Christian bookstore is the same as when it was

first penned? We will attempt to answer these questions in the following

study. D. There

are three major parts to the subject, "How We Got Our Bible." The

first part is Inspiration, the second is Canonization, and the third is

Transmission. Inspiration is how God gave His Word to man. Canonization is

how man collected God's Word. Transmission is how man transmitted that word

to succeeding generations. II. DEFINITION OF INSPIRATION A. Inspiration is the first and most

important part of this study. Furthermore, Canonization and Transmission are

hinged upon Inspiration. Without Inspiration, not only would it be pointless

to go on in our study, but the other two parts would not even exist.

Inspiration, simply defined, tells us how God gave us His Word. B. The

Webster's Dictionary defines inspiration this way concerning sacred

revelation, a divine influence or action on a person believed to qualify

him or her to receive and communicate sacred revelation. C. A

better definition of Inspiration is found in the Scriptures, particularly in

2Ti 3:16, where it says, All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable

for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness. D. The word, "inspired," is the

Greek word, theopneustos and literally means, "God-breathed"

(theos - God & pneustos - spirit or breath). The

idea is that the Scriptures have been God-breathed which means they originate

from God and comprise His inerrant Word. E. Definitions for Inspiration are: 1. The Bible is God's Word in the sense that

it originates with Him and is authorized by Him. (Geisler and Nix, "General

Introduction To The Bible", p.28) 2. Inspiration (God-breathed), emphasizes

the exhalation of God, hence, spiration would be more accurate since it

emphasizes that Scripture is the product of the breath of God The Scriptures

are not something breathed into by God, rather, the Scriptures have been

breathed out by God (Moody

Handbook of Theology) 3. Inspiration

is God's superintending of human authors so that, using their own individual

personalities, they composed and recorded without error in the words of the

original autographs His revelation to man. (Ryrie, Basic Theology) 4. We

believe the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the verbally

inspired Word of God, the final authority for faith and life, inerrant in the

original writings, infallible and God-breathed ( 2Tim. 3: 16-17; 2 Peter 1:20,21). (GBC

Doctrinal Statement) III. EXTENT OF INSPIRATION A. To what extent are the Scriptures

inspired? What books or what parts are inspired? The extent of inspiration

reaches to every word of Scripture. . B. Jesus taught us the extent of inspiration

in Mat 5:18, For truly 1 say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not

the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is

accomplished. C. The

extent of inspiration in Scripture is found in the "smallest

letter." The smallest letter would represent the smallest letter in the

Hebrew alphabet (yod or jot). The "smallest stroke" would be the

little brush stroke, that resembles a horn (lit.), used to distinguish Hebrew

letters. D. This

verse teaches us that every word of the Bible is inspired and is attributed

as God's Word. In fact, even the smallest letter will be fulfilled before

heaven and earth disappear. IV. PROCEDURE OF INSPIRATION A. A question that is always raised is,

"How can it be God's Word if men wrote it?" B. First

of all, God indeed did write down His Word with His own finger. In Ex. 31:18,

God inscribed the Ten Commandments on two tablets of stone by the

"finger of God". C. Secondly, God also dictated the Scriptures

to Moses when God said, "Write these words down" (Ex. 34:27). D. The

two examples teach us that the finished product of Scripture is equivalent to

God's Word. However, the procedure of inspiration is a little different than

the last two examples though the outcome is the same. E. Through the process of inspiration, the

Scriptures were written by the use of the writer's own personality and

circumstances, yet he was guided by the Holy Spirit. F. 2Pe

1:20-21 teaches us how the Scriptures are God's Word even though He used

human agents, But know this first of all, that no prophecy of Scripture is

a matter of one's own interpretation, 21 for no prophecy was ever made

by an act of human will, but men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God. G. Men

of God (prophets and apostles) were moved by the Holy Spirit to speak

and write (Rom 1:2) God's Word. H. The

word "moved" (pheromenoi - pres pass part -lit.

"being carried along"), was used in regards to ships that were

moved and carried by the gusts of wind. In the same way, the "holy men

of God" (literally) were mysteriously prompted and moved to write God's

Word, while at the same time maintaining their personalities and

circumstances. The final result was the inerrant, and infallible Word of God

(cp. 2Pe 3:15-16). V. AUTHORSHIP OF INSPIRATION A. One passage that is very important when

discussing the authorship of Inspiration is, 1Th 2:13. This verse calls

Scripture the "word of God," For this reason we also constantly

thank God that when you received the word of God which you heard from us, you

accepted it not as the word of men, but for what it really is, the word of

God, which also performs its work in you who believe. B. There

are three interesting points in this verse. First of all, the Thessalonians

were receptive to Paul's message from the Scriptures as the Word of God. Some

people do not receive the Bible as God's Word; they view the Bible as any

other ordinary book with contradictions and errors. C. Secondly,

the Thessalonians did not accept the Scriptures as the "word of

men." In other words, even though it was written by men, they believed

God watched over the writing of His Word. The finished product was not man's

thoughts, but rather God's thoughts and very words. Paul confirmed that in

reality (alethos - truthfully), it actually is the Word of God. D. Thirdly,

Paul says that it is God's Word that is, "at work in you who

believe." The Word of God alone is "living and active" (Heb

4:12; Eph 6:17b; Joh 15:7). Certainly some of the writings of men inspire us,

but it is only God's Word that is inspired (God-breathed). In addition, it is

only God's Word that changes our lives completely, giving us life through the

message of Christ's death on the cross (In 5:24; 6:68; Rom 10:17). VI. CONCLUSION A. Since inspiration is the most important

part to the subject, "How We Got Our Bible", we must have an

undeniable faith that the Bible is God's Word. Not only is it imperative for

this study, but it is preeminently paramount for the Christian Faith. B. Take away

inspiration out of the Bible and you are only a small step away from denying

Christ's death for sinful man. Take away Christ's death for sinful man, and

you take away the only name under heaven given to men by which he must be

saved. “HOW WE GOT OUR BIBLE” (PART

2 - CANONIZATION) Pastor I. THE

DEFINITION OF CANON A. Once

inspiration is determined as a foundational tenet, then we can begin to look

at canonization. Simply put, canonization is how man collected the inspired

Word. Inspiration has to do with the Bible’s authority, while canonization

has to do with the Bible’s acceptance. In other words, canonization is

concerned with the recognition and collection of inspired Scriptures. B. What exactly does canon mean? “Canon” comes from the Greek word kanw,n kanon, and literally means a rod or bar, straight or

measuring. 1. It

was used for staves to preserve the shape of the shield. It was also used as

a rule or straight-edge by shipbuilders and carpenters. a) [It

is used] in shipbuilding and house-building, and many other branches of

wood-working. For the artisan uses a rule (kanon), I imagine, a lathe,

compass, a chalk-line. (Plato

Philebus 56b) 2. This

Greek word very possibly came from the Hebrew word hn<q' qaneh, which means reed. In Ezek 40:3 it is

used as a “measuring rod.” 3. Later, the word took on the metaphorical

meaning rule as a “standard or norm”. The apostle Paul used this word in

Galatians 6:16 to represent a “rule” or “standard” by which to walk. a) Peace

and mercy to all who follow this rule (kanon), even to the 4. From

there, the word’s meaning was extended in the early Christian era when it was

applied to “authoritative Scriptures”. The first clear statement where kanon

was used for the authoritative Scriptures appears as early as A.D. 350 by

Athanasius. a) ...it

seemed good to me also, having been urged thereto by true brethren, and

having learned from the beginning, to set before you the books included in

the Canon, and handed down, and accredited as Divine...[in the same letter, Athanasius pronounced

all 27 books of the New Testament as canon in A.D 367] C. After that

time, the word “canon” was emphatically applied to the authoritative and

inspired Scriptures. The use of “canon” was expanded to other meanings such

as the “registrar of Roman Catholic saints” and also “church teaching”.

However, the real impact of this word upon history and religion surrounds its

meaning concerning which writings are recognized as inspired and those which

are not. D. Canon then means the standard by which the

Church regards books of the Bible as authoritative and divine. II. GOD IS THE

DETERMINER OF CANON A. Before going

any further, we must grasp one very important concept. That being the fact

that God was the “determiner” of canon, while man is simply the “discoverer”.

What exactly is meant by that? A book is determined canonical not because the

church or any man deems it so, rather it is canonical because God inspired

it. B. Determining which books are inspired was

God’s responsibility. God either inspired a particular book or he did not. It

is not as though the church or any man came along and said, “Oh I like this

one, it shall be called inspired (canon)”, or “This book inspired me, so

let’s call it inspired (canon)”. C. Thus, it could be said that the church is: 1. not

the “determiner” of canon, but the “discoverer” of canon; 2. not the “mother” of canon, but the

“child” of canon; 3. not the “regulator” of canon, but the

“recognizer” of canon; 4. not the “judge” of canon, but the

“witness” of canon. D. The

authority of the Scriptures is not founded, then, on the authority of the

Church: It is the Church that is founded on the authority of the Scriptures. (Louis Gaussen, Theopneustia, p.

137.) III. THE CHURCH IS

THE DISCOVERER OF CANON A. The next

question is, “What standard(s) did the church or men use to discover canon?”

While a list of standards was never found from the early church Fathers, we

can deduce certain principles used by them. There are at least five

questions: Is the book…? 1. Authoritative

- did it come with the authority of God, i.e. “thus saith the Lord”? 2. Prophetic - was it written by a man of

God, i.e. God’s mouthpiece? 3. Authentic - did it teach the truth about

God, i.e. His character and will? 4. Dynamic - did it have life-changing

power, i.e. “living and active”? 5. Received - was it accepted by God’s

people, i.e. true believers? B. The

characteristics sought by these questions were the earmarks of inspired

books. If they were apparent, the book was accepted. If they were absent, the

book was rejected. If they were not apparent, the book was doubted until it

was fully tested.

(Geisler and Nix, General Intro to the Bible, 138) C. The five questions discussed in detail for

discovering canon are: 1. Authoritative a) The

first question is, “Was it authoritative?” This is perhaps the most important

and fundamental question of them all. If a writing is not authoritative, it

does not mean that the book is useless, but it dogmatically is not the Word

of God! b) Some of the characteristic phrases that

qualify a writing as authoritative were: (1) “thus

saith the Lord” (KJV; 415 times in OT; Exo 4:22 cp. 5:1; Jdg 6:8; Isa 7:7; Ez

2:4...122 times) (2) “And the word of the Lord came to...” (103

time in OT; Isa 38:4; Jer 1:2) (3) “God spoke...” (Ex 3:14; Jonah 4:9) c) When

dealing with the canonicity of some of the prophets, where these phrases were

used, it hardly became necessary to look for other characteristics of

canonicity. On the other hand, some books were rejected by all, on the basis

that they had no such authoritative phrases, such as the Pseudepigrapha

(non-canonical writings with falsely accredited authors). d) It was with this same principle that some

doubted the book of Esther. For there is no mention whatsoever of the name of

“God” in the book of Esther, let alone the phrase, “thus saith the Lord”.

However, after much scrutiny the early church Fathers were convinced that

Esther was canon based upon the other standards, and thus its authority was

accepted. (1) In

a brief defense of Esther, even though God’s name is not used, His hand and

providence were manifested on behalf of the Jewish people. (2) Secondly, some claim that the reason God’s

name was left out was because being exiled, the covenant name of God was not

associated with the Jews anymore. (3) Others claim that God’s name was not

mentioned to protect it from pagan plagiarism by the substitution of a

heathen god. (4) An interesting note by W.G. Scroggie claims

that the name Yahweh (YHWH) is found acrostically in the book in such a way

that it is beyond probability that it was a coincidence.) (5) The book of Esther has brought both comfort

and conviction to the people of God, and has been accepted as a divinely

inspired book. e) The

bottom line is, however, that the cautiousness of the early church Fathers,

actually confirmed that these men included no book that God wanted excluded

from canon, and included only those which they were sure were authoritative. 2. Prophetic a) The

next question for the standard for canon was, “Was it written by a man of

God?” b) This is a vitally crucial basis in

discovering who actually penned the words of God. As already mentioned from 2

Peter 1:20-21, prophets, were men of God, who were “carried along” and moved

by the Holy Spirit to write God’s Word. These words did not originate (they

were not from the prophet’s own” interpretation” or lit. “unraveling or

disclosure”) from these men, but these men were specially called by God to be

the vehicle of them. c) This explains the many instances in the

Old Testament where the phrase is used, “and the word of the Lord came

to....” There were only certain men chosen by God to whom His actual word

came to. d) However, to give credence and

infallibility to God’s Word, God proclaimed a prophetic test. This test would

sort out the true from the false prophets. The test was that everything this

prophet said must absolutely come to pass. If it did not, the false prophet

was stoned because he did not carry God’s infallible Word. (1) NAU

Deu 18:20 'But the prophet who speaks a word presumptuously in My name which

I have not commanded him to speak, or which he speaks in the name of other

gods, that prophet shall die.' 21 "You may say in your heart, 'How will

we know the word which the LORD has not spoken?' 22 "When a prophet

speaks in the name of the LORD, if the thing does not come about or come

true, that is the thing which the LORD has not spoken. The prophet has spoken

it presumptuously; you shall not be afraid of him. e) This

test accomplished two things. One it assured the people which was God’s word

and which was not. (The original concept of canonization began with God!).

And two, it gave the people confidence to obey God’s Word. In fact, once the

people knew it was God speaking through the prophet, they were accountable to

obey, because they were in every sense, obeying God. (1) NAU

Deu 18:19 'It shall come about that whoever will not listen to My words which

he shall speak in My name, I Myself will require it of him. f) This

same principle was recurrent in the New Testament with the apostles. They

were to be the spokesmen of God’s infallible Word. They, like the prophets,

had God’s exclusive truth. Bearing this in mind, what a powerful statement it

was for Peter to make about Paul’s writings. (1) NAU

2Pe 3:16 as also in all his [Paul’s] letters, speaking in them of these

things, in which are some things hard to understand, which the untaught and

unstable distort, as they do also the rest of the Scriptures, to their own destruction. g) So,

according to Peter, Paul’s writings were equivalent to divinely inspired

Scriptures. But this was not only true for Paul, but also for Peter, John,

Matthew, James and Jude. It would also include Mark and Luke, who, although

not apostles, were under the tutelage of the apostles and chosen by God to be

a vehicle for His inspired Word. 3. Authentic a) The

next standard of canon is authenticity. The question that the Early Church

Fathers asked was, “Does this book tell the truth about God, Christ, man,

salvation etc?” If the book did not completely agree with other revealed

truths from God’s Word, it was rejected. b) This close scrutiny was passed on from the

apostles themselves, who were always defending the truth. John gives clear

instructions to “test the spirits” in light of their present day false

prophets. (1) NAU

1Jo 4:1 Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see

whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the

world. c) This

discernment for God’s revealed truth was naturally handed down to the early

church. A clear example of this is with the Bereans who respectfully

“examined” Paul’s teaching to ensure that he was an apostle with God’s truth. (1) NAU

Act 17:11 Now these were more noble-minded than those in Thessalonica, for

they received the word with great eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily

to see whether these things were so. d) Without

a doubt, the seed was planted for the Early Church Fathers to be on guard

when it came to accepting anything as God’s truth. Their motto was kind of

“If in doubt, throw it out”, a policy that we would be wise for using in

today’s church. Not for determining canon, that has been done for us, but

rather for discerning truth from false doctrine. 4. Dynamic a) Yet

another standard was applied to ascertaining canon from non-canon writings.

This standard was a question of dynamics. The question that could have been

asked was, “Does this book come with the power of God?” In other words, God’s

Word is dynamic; it is “living and active”. b) That means God changes lives through His

Word by the power of His Spirit. If that could not happen, then a book was

rejected. This was recognized by Paul when he wrote to Timothy: (1) NAU

2 Timothy 3:15 and that from childhood you have known the sacred writings

which are able to give you the wisdom that leads to salvation through faith

which is in Christ Jesus. (a) An

interesting note is that the Greek word for “able” here in this passage is dunamai

which means ability or power. We get our English word “dynamite” from this

word. (b) The Scriptures have dynamic power because

they are inspired by God and it is the instrument used by the Holy Spirit

(Eph 6:17; Ps 19:7) to change the lives of believers. And as Paul shares with

Timothy, the Scriptures enable man to know God’s plan for salvation. c) A

book cannot have the power to change lives or convert the soul if the book

contains errors. Many passages in the Bible are written in a “cause and

effect” formula. Only a Sovereign God has the ability to bring about such

effects. Man often attempts to diagnose life, but unless he is using God’s

Word as a guideline, he is shooting in the dark. d) But only heaven will reveal the untold

number of martyrs and of troubled believers that have been comforted,

solaced, and encouraged through the Scriptures. Geisler and Nix state it

well: (1) A

message of God would certainly be backed by the might of God. 5. Received a) The

capstone of all these standards would be in the reality of whether or not a

book has been received by the people of God. The question that could have

been asked was, “Has this book been accepted generally by the people of God?” b) First of all, when speaking of the people

of God, what is meant, is the true believing church. We certainly would not

include heretical groups or unbelievers, such as Marcion the Gnostic,

(100-160)who rejected the Old Testament and almost all of the New Testament

(a revised Luke and ten of Paul’s epistles, but not the Pastorals). And as

already sited, Peter, writes of

unbelievers who reject the Scriptures (2 Pet 3:15). c) Secondly, all non-canonical books were

more or less rejected by this standard. If a book did not stand the test of

time and acceptance, it was eventually rejected. Initially, the books were

accepted by the recipients, such as in the case of the Thessalonians. (1) And

we also thank God continually because, when you received the word of God,

which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men, but as it

actually is, the word of God, which is at work in you who believe. (1

Thessalonians 2:13). d) As

these books were cherished and collected, they were also copied and passed on

to succeeding generations. Over a period of time, some of these books, were

universally accepted. (1) Most

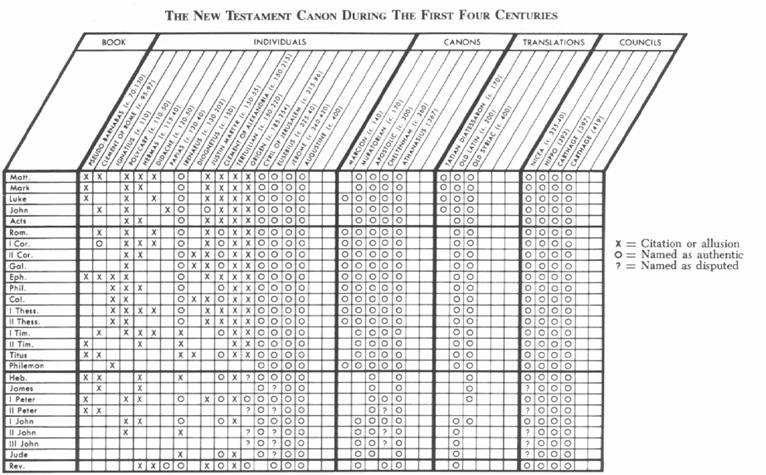

of the canon was well known and in use nearly two centuries before (2) …some [early church] Fathers and canons

recognized almost all of the books before the end of the second century, and

the church universal was in agreement before the end of the fourth century. (Geisler & Nix, General Intro to

the Bible; pg. 291). (3) Irenaeus (c. A.D. 170), [was] the first

early [church] Father who himself quoted almost every book of the New

Testament. (ibid. pg.

292). (4) Clement of e) Some

books were so unanimously accepted that when men like Marcion opposed them,

they were met with fierce and instantaneous opposition. (1) In

like manner, too, he dismembered the Epistles of Paul...and also those

passages from the prophetical writings which the apostle quotes... (Iraneus,

Early Church Fathers, Vol 1, p 726) (2) At least as early as A.D. 140 the heretical

Marcion accepted only limited sections of the full New Testament canon.

Marcion’s heretical canon, consisting of only Luke’s gospel and ten of Paul’s

epistles, pointed up clearly the need to collect a complete canon of New

Testament Scriptures.

(Geisler & Nix, General Intro to the Bible; pg. 278) f) These

standards then, were the earmarks for the early church with which to

recognize the books God had inspired and those which He had not. When

discovered, they were added as the authoritative, prophetic, dynamic,

authentic and accepted canon, namely the Word of God.

“HOW

WE GOT OUR BIBLE” (PART

3 - TRANSMISSION) Pastor I. INTRODUCTION A. From

the original autograph to the modern Bible extends an important link in the

overall chain from “God to us” known as transmission. (Geisler & Nix, General Introduction

To the Bible) B. It provides a credible answer to the

question: Do Bible scholars today possess an accurate copy of the autographs?

(ibid) C. In support of the integrity of the

transmission, an overwhelming number of ancient documents must be presented. (ibid) D. There are not only countless manuscripts

to support the integrity of the Bible (including the Old Testament since the

discovery of the E. For the New Testament, beginning with the

second century ancient versions and manuscript fragments and continuing with

abundant quotations of the Fathers and thousands of manuscript copies from

that time to the modern versions of the Bible, there is virtually an unbroken

line of testimony. (ibid) F. In fact, it may be concluded that no major

document from antiquity comes into the modern world with such evidence of its

integrity as does the Bible. (ibid) II. ORIGINAL

AUTOGRAPHS A. “Original

autographs” are the very originals that were penned by the prophets and

apostles or their amanuenses (i.e. scribal secretary - Jer 36:27; Rom 16:22;

Gal 6:11). These are the writings that were under the divine process of

inspiration. When the autographs went from the originals to copies, the

process is not called, “inspiration,” but “transmission.” Therefore, the

divine process of inspiration only applies to the original autographs. B. It is almost universal among evangelical

orthodox individuals and churches to make such distinction in their position

and doctrinal statements. 1. We

do not assert that the common text, but only that the original autographic

text, was inspired.

(Archibald A. Hodge and Benjamin B. Warfield, Inspiration, pg. 42) 2. The original autographs of the Scriptures

were infallibly correct.

(John R. Rice, Our God-Breathed Book -- The Bible, pg. 88) 3. We believe the Holy Scriptures of the Old

and New Testaments to be the verbally inspired Word of God, the final

authority for faith and life, inerrant in the original writings, infallible

and God-breathed. (II Tim. 3:16-17; II Peter 1:20,21). ( 4. “All Scripture is given by inspiration

of God" (2 Tim.3:16), by which we understand that holy men of God

"were moved by the Holy Spirit" to write the very words of

Scripture (2 Pet.1:21). This divine inspiration extends equally and fully to

all parts of the sixty-six books of the Bible as it appeared without error in

the original manuscripts (Jn.10:35; Mt.5:18). ( 5. Thus, the orthodox doctrine that the

Bible is the infallible, inerrant Word of God in its original manuscripts has

maintained itself from the first century to the present. (Geisler, N. L., & Nix, W. E.

(1996, c1986). A General Introduction To The Bible, pg. 156). C. The copies

that we possess cannot be technically said to be inspired. However, because

we possess copies of the inspired original that are 98-99.9% pure, our copies

can be considered “virtually” inspired. 1. The

Bible obviously did not come to us in its present form. Rather, as God

inspired its human authors His words were written down in scrolls. These

original manuscripts (or autographs as they are sometimes called) contained

no errors, presenting perfectly the Word of God. However, there are no known

originals left. What we possess today are thousands of copies of the original

manuscripts (this includes fragments, which in some cases may contain only a

verse or two). The problem is that while the manuscripts we study today agree

to an incredible extent there do exist differences. (Rev. Gary Gilley, Southern View Chapel) 2. It is comforting to note, however, that

scholars estimate that the text we have before us is between 98 and 99.9%

pure — exactly as originally written. Only about 50 readings of any

significance is in doubt, and none of these affect any basic doctrine. So we

can have complete confidence in our text. (Rev. Gary Gilley, Southern View Chapel) 3. Strictly speaking, only the

"Autographs" (the original documents penned by the biblical

authors) are inspired. (Copies of the original documents are VIRTUALLY

inspired to the extent that they accurately reflect the original

documents--and the evidence indicates that they DO accurately reflect the

original documents to a very high degree.) (Ron Rhodes, The Complete Book of Bible Answers) 4. No one manuscript or translation is

inspired, only the original. However, for all intents and purposes, they are

virtually inspired since, with today's great number of manuscripts available

for scrutiny, the science of textual criticism can render us an adequate

representation. Therefore, we can be assured that when we read the Bible we

are reading the inspired Word of God. (Josh McDowell, Don Stewart, Reasons Skeptics Should Consider

Christianity) III. PRESERVATION

OF TRANSMISSION A. The Old

Testament manuscripts fall into two general periods of evidence. 1. The

Talmudic Period (c. 300 B.C.–A.D. 500) a) By

the time of the Maccabean revolt (168 B.C.), the Syrians had destroyed many

of the existing manuscripts of the Old Testament. b) The Talmudic period produced many

manuscripts which were preserved in synagogues and by private owners. c) In addition, The Dead Sea Scrolls (c. 167

B.C.–A.D. 133) have made an immense contribution to Old Testament critical

study. 2. The

Masoretic Period (A.D. 500-1000) a) Masoretes

are Jewish textual scribes of the fifth through ninth centuries A.D. who

standardized the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, which is therefore called

the Masoretic Text. b) The Masoretes understood the significance

of God’s revelation to man in the form of the Scriptures. Because of such

understanding, they were meticulous in copying the Scriptures. In fact, they

had incorporated rules to guarantee that there were no errors in the

transmission process. Samuel Davidson, in “The Hebrew Text of the Old

Testament, p. 89, writes of these rules: [1] A synagogue roll must be written on the

skins of clean animals, [2]

prepared for the particular use of the synagogue by a Jew. [3] These

must be fastened together with strings taken from clean animals. [4] Every

skin must contain a certain number of columns, equal throughout the entire

codex. [5] The

length of each column must not extend over less than 48 nor more than 60

lines; and the breadth must consist of thirty letters. [6] The

whole copy must be first-lined; and if three words should be written without

a line, it is worthless. [7] The

ink should be black, neither red, green, nor any other colour, and be

prepared according to a definite recipe. [8] An

authentic copy must be the exemplar, from which the transcriber ought not in

the least deviate. [9] No

word or letter, not even a yod, must be written from memory, the scribe not

having looked at the codex before him. . . . [10]

Between every consonant the space of a hair or thread must intervene; [11]

between every new parashah, or section, the breadth of nine consonants; [12]

between every book, three lines. [13] The

fifth book of Moses must terminate exactly with a line; but the rest need not

do so. [14]

Besides this, the copyist must sit in full Jewish dress, [15] wash

his whole body, [16] not

begin to write the name of God with a pen newly dipped in ink, [17] and

should a king address him while writing that name he must take no notice of

him. B. The New

Testament manuscripts fall into four general periods of evidence. 1. 1st-3rd

Cent. a) The

first three centuries witnessed a composite testimony as to the integrity of

the New Testament Scriptures. Because of the illegal position of

Christianity, it cannot be expected that many, if any, complete manuscripts

from that period are to be found. (Geisler, N. L., & Nix, A General Introduction To The

Bible). b) Therefore, textual critics must be content

to examine whatever evidence has survived, that is, nonbiblical papyri,

biblical papyri, ostraca, inscriptions, and lectionaries that bear witness to

the manuscripts of the New Testament . (ibid.) 2. 4th-5th

Cent. a) The

fourth and fifth centuries brought a legalization of Christianity and a

multiplication of manuscripts of the New Testament. (ibid.) b) These manuscripts, on vellum and parchment

generally, were copies of earlier papyri and bear witness to this dependence.

(ibid.) 3. 6th-10th

Cent. a) From

the sixth century onward, monks collected, copied, and cared for New

Testament manuscripts in the monasteries. (ibid.) b) This was a period of rather uncritical

production, and it brought about an increase in manuscript quantity, but with

a corresponding decrease in quality. (ibid.) 4. 11th

Cent on a) After

the tenth century, uncials (“inch high” formally printed large letters) gave

way to miniscules (small cursive letters), and copies of manuscripts

multiplied rapidly.

(ibid.) C. Comparison to

Classical Greek Manuscripts a) The

classical writings of b) The abundance of biblical evidence would

lead one to conclude with Sir Frederic Kenyon that “the Christian can take

the whole Bible in his hand and say without fear or hesitation that he holds

in it the true word of God, handed down without essential loss from

generation to generation throughout the centuries.” (ibid.) c) Or, as he goes on to say, The number of

manuscripts of the New Testament, of early translations from it, and of

quotations from it in the oldest writers of the Church, is so large that it

is practically certain that the true reading of every doubtful passage is

preserved in some one or other of these ancient authorities. This can be said

of no other ancient book in the world. (ibid.) “HOW

WE GOT OUR BIBLE” (PART

4 - TRANSLATION) Pastor I. GREEK

MANUSCRIPTS A. Four Main

Branches Of Manuscript Traditions 1. As

the church became more established, certain definable New Testament manuscript

traditions tended to become the standards within more or less defined areas. (Gilley, The Bible Translation Debate) 2. These became known as

"text-types" and there were four of them (ibid.). a) The

Byzantine text: Preserved by the b) The

Western text: Sprang from fairly undisciplined scribal activity, and

therefore, considered the most unreliable of the "text-types” (ibid.). c) The

Alexandrian text: Prepared by trained scribes, most likely in d) The

Caesarean text: Probably originated in B. Two Major

Texts of Controversy (Textus Receptus vs. Wescott and Hort) 1. Textus

Receptus (KJV) a) In

1516, Erasmus, a Roman Catholic Priest and humanist, was pressured into to

finishing a Greek text in order to be the first Greek text published. b) Erasmus was only able to acquire about six

Byzantine manuscripts (out of thousands and none of which was written before

the sixteenth century) from which to groom a reliable Greek text. c) After its first publishing, Erasmus and

others would end up revising the text many times. d) In 1611, The KJV was translated from one

of Erasmus’ revisions. e) In 1633, another revision was published

by Erasmus, which contained the words, “Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus

receptum: in quo nihil immuta tum aut corruptum damus.” (“The reader has

the text which is now received by all, in which we give nothing changed or

corrupted.” cf. Metzger, The Text of

the New Testament, p. 106.) Thereafter, this newest revision of the Greek NT

was coined, the "received text," or the "Textus

Receptus." (1) Note

that it was not “received” in the sense that God was putting his stamp of

approval upon this Greek revision alone. (2) It was received in that it was considered

the standard text of that time. f) Two

points of interest (1) Erasmus

had no Greek manuscripts for the last six verses of Revelation, so he

back-translated from Latin to Greek. (2) Erasmus, included in later revisions, the

phrase written by a scribe in the margin of 1Jo 5:7-8, the Father, the

Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. (a) A.T.

Robertson comments: (i) The

last clause belongs to verse 8. The fact and the doctrine of the Trinity do

not depend on this spurious addition. (in loc. Word Pictures) (ii) Some Latin scribe caught up Cyprian's

exegesis and wrote it on the margin of his text, and so it got into the

Vulgate and finally into the Textus Receptus by the stupidity of Erasmus (ibid.). (b) John

MacArthur Jr. comments: (i) These

words are a direct reference to the Trinity and what they say is accurate.

External manuscript evidence, however, is against them being in the original

epistle. They do not appear in any Gr. mss. dated before ca. tenth century

a.d. Only 8 very late Gr. mss. contain the reading, and these contain the

passage in what appears to be a translation from a late recension of the

Latin Vulgate. Furthermore, 4 of those 8 mss. contain the passage as a

variant reading written in the margin as a later addition to the manuscript. (ii) No Greek or Latin Father, even those

involved in Trinitarian controversies, quote them; no ancient version except

the Latin records them (not the Old Latin in its early form or the Vulgate).

Internal evidence also militates against their presence, since they disrupt

the sense of the writer’s thoughts. Most likely, the words were added much

later to the text. There is no verse in Scripture which so explicitly states

the obvious reality of the Trinity, although many passages imply it strongly. 2. Wescott

and Hort (Most modern translations) a) In

1881, after about thirty years of labor, B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort

published a famous Greek New Testament. b) Westcott and Hort, liberal scholars,

argued that the later manuscripts (Byzantine) were inferior to the older

manuscripts (Alexandrian). (1)

In their work, the scholars used manuscripts that dated back to the second

century, some 600 years earlier than anything used by Erasmus. As a basis

they used two manuscripts — the Vaticanus and the Sinaiticus. These works are

believed by many to be the finest and most complete NT manuscripts known to

exist. (Gilley, The

Bible Translation Debate). c) While

neither text is without flaw, most modern translators have chosen Westcott

and Hort because of the careful scholarship in light of recent discoveries.

In all fairness to Erasmus, a large amount of manuscripts were unavailable to

him because they had not been discovered. Had they been available to Erasmus,

there is little doubt that he would have scrutinized and evaluated them all

as did Westcott and Hort. d) When the actual variations between the

Textus Receptus, Westcott and Hort, and the 26th edition of the

Nestles-Aland Greek texts, the vast majority of variations are so minor that

they are not even translatable, (the most common is the moveable “nu”, which

is akin to the difference between ‘who’ and ‘whom’). (1) Dan

Wallace comments: (a) When

one compares the number of variations that are found in the various MSS with

the actual variations between the Textus Receptus and the best Greek

witnesses, it is found that these two are remarkably similar. There are over

400,000 textual variants among NT MSS. (b) But the differences between the Textus

Receptus and texts based on the best Greek witnesses number about 5000—and

most of these are untranslatable differences! In other words, over 98% of the

time, the Textus Receptus and the standard critical editions agree. 3. Conspiracy

Theories a) There

are legitimate questions as to which Greek text is the most reliable. b) However, the question must be answered by

legitimate and careful scholarship in view of all the evidence. Not by sharp

disagreements based on emotions and over-biased preferences that lead to

conspiracy theories. (1) Honest

disagreement still remain concerning which Greek NT is superior. However,

among those who love God’s Word there is no conspiracy or attempt to corrupt

the Word of God. I believe that all manuscripts can be used and studied, and

as was stated earlier, we can have complete confidence in the Bible that is

in our hands. (Gilley,

The Bible Translation Debate) (2) Those who vilify the modern translations

and the Greek texts behind them have evidently never really investigated the

data. Their appeals are based largely on emotion, not evidence. As such, they

do an injustice to historic Christianity as well as to the men who stood

behind the King James Bible. These scholars, who admitted that their work was

provisional and not final (as can be seen by their preface and by their more

than 8000 marginal notes indicating alternate renderings), would

wholeheartedly welcome the great finds in MSS that have occurred in the past

one hundred and fifty years. (Dan Wallace) II. MODERN

TRANSLATIONS A. Historical

View of Bible Translation 1. Up

until the twentieth century, there has been only one identifiable philosophy

of Bible translation, namely a literal translation of the original Hebrew and

Greek texts. 2. Around the middle of the twentieth

century, a new philosophy emerged. This philosophy attempted to reproduce not

the words of the original text but the thoughts and ideas. The leading

proponents behind this philosophy were Kenneth Pike and Eugene Nida. B. Philosophies

of Bible Translations 1. The

name of the historical philosophy of translation is called, “Formal

Equivalence” which seeks to carefully translate word-for-word. It is also

known, as “Literal Translation.” 2. The name of the more modern philosophy is

called, “Dynamic Equivalence.” This philosophy seeks to capture the thoughts,

meanings, and ideas of the original texts. “Dynamic Equivalence” was the

impetus for translation on the mission fields and was carried over to the

retranslation of the English Bible. 3. Another philosophy of translation is

called, “Paraphrase” which is simply a restatement of a text in another form

or other words, often to clarify meaning. 4. Still another philosophy is called, “Free

Translation” which seeks to combine word-for-word and thought-for-thought

translations (i.e. NET Bible). C. Pros and Cons

of Formal Equivalence (FE) 1. Pros a) FE

assures the reader that the translation is as close to the original as is

allowable in translating from one language into another. b) FE allows the reader to interpret the

meaning of the original text and not the translators for him. c) FE assures theological precision in

preserving theological concepts through theological vocabulary. d) FE eliminates the need for translation

correction in teaching and preaching. e) FE assures the original author’s

scholarship and literary style (i.e. play on words) 2. Cons a) Sometimes

translating word-for-word can create greater ambiguity with idioms and

colloquialisms. b) If the translation is too difficult

because it is literally translated, then there will be less interest to read

it. c) Unless an individual is a bible student,

he may have difficulty interpreting Scripture accurately. D. Pros and Cons

of Dynamic Equivalence (DE) 1. Pros a) DE

changes words that are deemed old-fashioned or difficult into more

contemporary and colloquial language. b) DE simplifies difficult metaphors into

direct statements for the reader’s understandability. c) DE turns long choppy sentences into

shorter comprehensible sentences. d) DE reduces the level of vocabulary to a

level suitable to the ability of today’s readers 2. Cons a) If

original writers would have wanted their text simplified, they could have

written it differently. b) If God would have wanted the original

writers to write differently, they he would have moved them to write

differently. c) Not all scholars agree on the meanings of

words so there can be multiple translations and interpretations. d) E. Problem

Examples 1. Rom

1:5 a) Through

him and for his names sake, we received grace and apostleship to call people

from among all the Gentiles to the obedience that comes from faith (NIV). b) Jesus was kind to me and chose me to be

an apostle, so that people of all nations would obey and have faith (CEV). c) Through Christ, God has given us the

privilege and authority to tell Gentiles everywhere what God has done for them,

so that they will believe and obey him, bringing glory to his name (NLT). d) Rom 1:5 through whom we have received

grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith among all the

Gentiles for His name's sake, (NASB) 2. John

6:27 a) .

. . for on Him the Father, even God, has set His seal (NASB) b) . . . . because God the Father has set His

seal on Him (NKJV). c) For on him God the Father has set his

seal (ESV). d) On him God the Father has placed his seal

of approval (NIV, TNIV) e) . . . . for on him God the Father has set

the seal of his authority (REB). . . . because God the Father has given him

the right to do so (CEV). f) For God the Father has sent me for that

very purpose (NLT). g) He and what he does are guaranteed by God

the Father to last (The Message). 3. Ps

1:1 a) …nor

standeth in the way of sinners (KJV, NIV, ESV, RSV, ASV, DBY) b) … Nor stand in the path of sinners (NASB, NKJ, c) … stand in the pathway with sinners (NET) d) … take the path that sinners tread (NRS) e) … stand around with sinners (NLT) F. Conclusion 1. Based

on the Scriptures own teaching, it would support word-for word translations a) If

“every word of God” is tested and tried, then translations should reflect the

equivalent of every word (Pr 30:15). b) If Jesus declared that every jot and

tittle would be fulfilled, then translations must make sure that every word

is translated word-for-word (Mat 5:18). c) Man lives by every word of God (Mat 4:4). d) The Bible’s words are spirit words and

words of life (Joh 6:63; Deut 32:46-47). e) Man is not to add to the Scriptures (Deut

4:2; 12:32; Pr 30:6; Rev 22:18-19) 2. Expositional

teaching and preaching would support word-for word translations. 3. We must also realize that no translation

is a 100% word-for-word translation. It simply would be unreadable. 4. There are times when all versions must

adjust to idioms. 5. It may be helpful at times for the Bible

Student to read various translations to know about different views on a

particular passage. 6. Furthermore, we must be careful that we

do not blow the Bible version debate way out of proportion and neglect the

great duty to read the Scriptures daily. G. Addendum:

Identification of Philosophies of Translation in English Versions 1. Formal

Equivalence (Essentially word-for-word) a) NASB—New

American Standard Bible b) ESV—English Standard Bible c) KJV—King James Version d) NKJV—New King James Version e) RSV—Revised Standard Version f) NRSV—New Revised Standard Version 2. Dynamic

Equivalence a) NIV—New

International Version b) TNIV—Today’s New International Version c) NLT—New Living Translation d) CEV—Contemporary English Version e) GNB—Good News Bible 3. Paraphrase a) NTME—The

NT in Modern English (Phillips) b) TLB—The Living Bible c) TM—The Message d) TSB—The Street Bible |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|